Slow Oxidation (HTMA): When the Body Hits the Brakes

Ever wonder why some people run on steady energy while others feel stuck in slow motion? Hair Tissue Mineral Analysis (HTMA) helps explain this through your oxidation type and oxidation rate — how efficiently your body converts food into usable energy at the cellular level.

In Nutritional Balancing, there are four main oxidation-related patterns:

- Fast Oxidation: the metabolic engine is running hot and fast

- Slow Oxidation: the body applies the brakes to conserve energy

- Mixed Oxidation: shifting between fast and slow depending on stress and demand

- Four Lows Pattern: deep depletion, burnout, or a rebuilding phase

This page focuses specifically on slow oxidation — what it means, why it develops, how it appears on an HTMA, and how it is typically supported.

All information here is educational only and is not intended for diagnosis, treatment, or medical advice.

Article Contents

- Energy: Your Body’s Electricity

- What Is Oxidation Rate, Really?

- What Slow Oxidation Means

- Common Signs and Lived Experience

- Why Slow Oxidation Develops

- How Slow Oxidation Appears on an HTMA

- What Blood Tests and Symptoms Often Miss

- Degrees and Variants of Slow Oxidation

- How to Eat for Slow Oxidation (and Why It Works)

- Lifestyle Support for Slow Oxidation

- Supplement Guidelines for Slow Oxidation

- Common Mistakes That Delay Recovery

- Retests, Shifts, and Accuracy Notes

- The Takeaway: From Conservation to Repair

Energy: Your Body’s Electricity

Energy isn’t just about sleep, motivation, or willpower. At a biological level, it is chemical.

As Dr. Paul Eck explained,

“It is the balance of the minerals within the body that controls the rate at which energy is produced and used.”

Minerals act like conductors in an electrical system. They influence how quickly fuel is burned, how the nervous system responds to stress, how stable blood sugar feels, and how well the body recovers.

Your oxidation rate describes the pace at which this internal system runs. When the rate is mismatched to your needs for too long, symptoms appear. HTMA offers a way to observe that pace through tissue mineral patterns rather than guesswork.

What Is Oxidation Rate, Really?

Oxidation rate refers to how efficiently the body converts food into energy inside the mitochondria.

It is influenced primarily by:

- adrenal gland activity

- thyroid cellular effect

- the balance between calcium, magnesium, sodium, and potassium

In Nutritional Balancing, oxidation type is categorized as fast or slow, while oxidation rate can be mild, moderate, or extreme within those types.

This page focuses on slow oxidation.

What Slow Oxidation Means

Slow oxidation is a state of body chemistry characterized by reduced adrenal and thyroid effect at the tissue level. This does not necessarily show up on standard blood tests.

It is often described as:

- a more yin, conservative metabolic state

- a system leaning parasympathetic by default, not because it is relaxed, but because sympathetic output is limited

- an exhaustion stage of stress, where the body prioritizes survival over output

- a state of reduced chaos, where variability and demand are lowered to protect remaining reserves

Not all slow oxidation is the same. In some people it reflects deep depletion. In others, it is a temporary conservation phase while the body reorganizes and repairs.

Slow oxidation is not failure. It is adaptation.

Common Signs and Lived Experience

Symptoms alone do not define oxidation type, but slow oxidation often presents with a recognizable cluster:

Energy and mood

- persistent fatigue or low stamina

- brain fog, slower thinking, reduced mental sharpness

- low motivation, emotional flatness, or feeling “heavy”

- reliance on caffeine or sugar just to function

Body and circulation

- cold hands and feet

- low or unstable blood pressure

- blood sugar dips between meals

- reduced sweating

Skin, hair, digestion

- dry skin and dry hair

- constipation or sluggish digestion

- bloating or heaviness after meals

Many conditions can exist in both fast and slow oxidation. What differs is the underlying physiology — and therefore what actually helps.

Why Slow Oxidation Develops

Slow oxidation usually emerges from long-term stress combined with depleted reserves.

Common contributors include:

- chronic physical or emotional stress without adequate recovery

- long-term under-eating or inconsistent meals

- diets low in nutrient density, especially protein and minerals

- digestive weakness and poor absorption

- prolonged stimulant use that creates short bursts of “false energy”

- toxic burden that the body cannot eliminate efficiently

- ongoing structural tension that keeps the nervous system braced

Over time, the body slows output not because it wants to — but because it must.

How Slow Oxidation Appears on an HTMA

On an unwashed hair sample, slow oxidation is typically identified when both of the following are present:

- Calcium / Potassium (Ca/K) ratio above 4

- Sodium / Magnesium (Na/Mg) ratio below 4.17

This often appears visually as:

- higher calcium and magnesium

- lower sodium and potassium

These patterns reflect reduced adrenal and thyroid effect at the tissue level.

Visual vs ratio-based patterns

Slow oxidation is often visually obvious — but not always.

When all four macrominerals are elevated (sometimes called a “four highs” look), visual interpretation can be misleading. In those cases, the ratios are essential for accurate classification.

What Blood Tests and Symptoms Often Miss

Blood serum minerals are tightly regulated and reflect short-term balance. Hair reflects longer-term storage and elimination patterns.

As a result:

- blood tests may appear normal while tissue energy is low

- symptom questionnaires can hint at patterns but are unreliable on their own

- HTMA offers a broader view of how the body has been adapting over time

This is why oxidation type is best assessed through hair, not symptoms alone.

Degrees and Variants of Slow Oxidation

Slow oxidation exists on a spectrum.

In general:

- higher Ca/K ratios reflect greater metabolic conservation

- lower Na/Mg ratios reflect reduced adrenal output

There are also common variants, including:

- slow oxidation with different sodium/potassium dynamics

- slow oxidation combined with Four Highs or Four Lows patterns

- autonomic imbalances where stress remains high despite low output

Retesting helps clarify direction. The goal is not labeling — it’s tracking recovery.

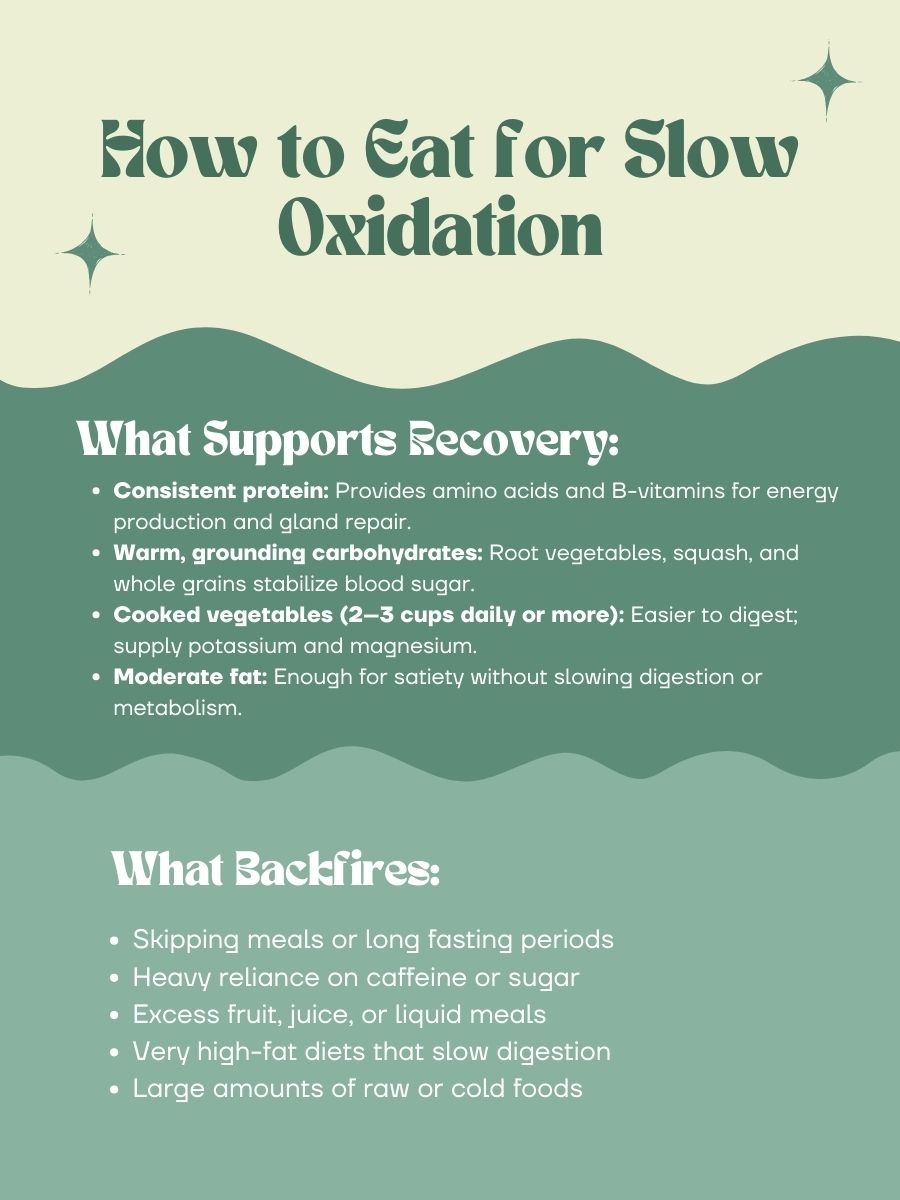

How to Eat for Slow Oxidation (and Why It Works)

The goal of diet in slow oxidation is rebuilding, not stimulation.

When oxidation is slow, energy production is already conservative. Meals that are too light, too cold, or too sugar-based often worsen instability rather than restore energy.

What supports recovery

Consistent protein

Protein supplies amino acids and B-vitamins needed for steady energy production and glandular repair.

Warm, grounding carbohydrates

Root vegetables, squashes, and whole grains help stabilize blood sugar and reduce reliance on stimulants.

Cooked vegetables (2–3 cups daily or more)

Provide potassium and magnesium while remaining easier to digest when metabolism is slow.

Moderate fat

Enough for satiety, but not so much that digestion and metabolic pace slow further.

A simple slow-oxidizer plate often looks like:

- protein + cooked vegetables + a grounding carbohydrate

What tends to backfire

- skipping meals or long fasting windows

- heavy reliance on caffeine or sugar

- excess fruit, juice, or liquid meals

- very high-fat diets that slow digestion further

- large amounts of raw or cold foods

The goal is steady fuel, not spikes.

Lifestyle Support for Slow Oxidation

- prioritize regular sleep and consistent meal timing

- choose gentle movement over intense or exhausting exercise

- build recovery into the week before a crash forces it

- reduce constant urgency and overstimulation

Slow oxidation often improves when the body feels safe enough to spend energy again.

Supplement Guidelines for Slow Oxidation

Supplement support should be individualized and adjusted with retesting.

General themes often include:

- targeted mineral support guided by ratios

- gentle adrenal and thyroid support — not stimulants

- digestive support to improve absorption

- avoiding unnecessary supplements that further “cool” the system

Consistency matters more than intensity.

Common Mistakes That Delay Recovery

- chasing energy with stimulants instead of rebuilding reserves

- under-eating protein or skipping meals

- pushing intense exercise to “force” metabolism

- making too many changes at once

- assuming high calcium on the chart means calcium is functioning well in cells

Retests, Shifts, and Accuracy Notes

Oxidation rate is not fixed.

- Retests often shift as mineral reserves rebuild.

- Hair preparation matters. Washing hair at the lab or showering with softened water can distort sodium and potassium readings.

- Blood tests and symptom checklists are not reliable indicators of oxidation rate.

The Takeaway: From Conservation to Repair

Slow oxidation does not mean your body is broken. It often means it has been carrying stress for a long time and has chosen conservation to survive.

Balancing slow oxidation usually involves:

- restoring mineral and energy reserves

- supporting digestion and absorption

- eating consistently and sleeping deeply

- reducing “false energy” strategies

- adjusting support based on HTMA retesting

As energy becomes more efficient and sustainable, the body can shift out of conservation and back into repair.